Featured Article:

-

“Mysteries, Epiphanies and the Friends You Keep” by Oliver DeMille

-

“Whose Job Is It?” by Rachel DeMille

TJEd NEWS:

* Texas TJEd Family Forum Saturday, June 2 in Round Rock (Austin), Texas!

* Youth for Freedom Summer Conferences 3 sessions to choose from!

******************

Featured Article:

Mysteries, Epiphanies, and the Friends You Keep

by Oliver DeMille

Old Friends

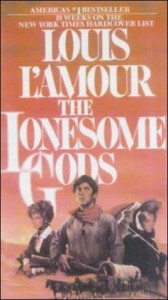

I browsed the list of book titles about reading and classics on Amazon today. I found a number of old friends. I’ve always considered books my friends since I read Louis L’Amour as a boy — many of L’Amour’s characters love reading and call their favorite books old friends, and I picked up that habit long before I left my parents’ home.

I browsed the list of book titles about reading and classics on Amazon today. I found a number of old friends. I’ve always considered books my friends since I read Louis L’Amour as a boy — many of L’Amour’s characters love reading and call their favorite books old friends, and I picked up that habit long before I left my parents’ home.

Later, in the home my wife and I were creating together, I found a visiting friend, Michael Platt, in front of my line of bookshelves scanning the titles.

He saw the various books of history, the shelves of classics, the political and economic commentaries, and the other collections on topics of interest. But he only commented on my long shelf with the tattered works of Louis L’Amour carefully arranged in alphabetical order. “L’Amour,” he said, then repeated, “L’Amour.”

I wondered what he was thinking.

New Friends

I first met Michael, or “Dr. Platt,” as thousands of students from schools around the nation know him, at an airport in Michigan. We were both on route to a seminar at Russell Kirk’s home, and we talked for hours at the airport and on the long rural drive.

Michael was educated in the classics at Harvard for his undergraduate and Yale for his graduate work, and I found him to have a deep and seemingly endless knowledge of what the great books had to say on any topic we discussed.

“L’Amour,” he said, nodding his head knowingly. Michael then told me you can tell a great deal about a person by the books he keeps and rereads like old friends. I don’t know whether he was sharing a L’Amourism with me or just his own perspective, but it was second witness of an important theme. Then he recommended The Virginian by Owen Wister.

Pioneers

Later that day, Michael took my mountain bike out to the flat west of our home and cut a bag of sagebrush to take home to his children. It started raining, so I drove the van out to rescue him from the downpour.

On the drive home, with the smell of fresh rain and sage, Michael and I talked about freedom and the modern American connection with the frontier times chronicled by L’Amour, Wister and Willa Cather. Most of L’Amour’s characters (or maybe just my favorites) work hard to build a new nation, boldly facing and overcoming numerous challenges along the way. And always they carry books with them.

They read by firelight or candlelight, or on occasion during a rare day of rest. They read Plutarch and Abelard, and many of the classics. And, invariably, they discuss what they have learned with others who read these same great works. The books, and the challenges of life, make the characters into better men and women.

Perhaps the most enduring lesson I learned from L’Amour’s books is that there are many ways to get an education. Books are an important part of learning — but only a part. Knowledge must be applied, and learning must become wisdom.

Students, and all of us, learn by doing. Again, this isn’t the only way to learn, but it is one of the most effective. The combination of books, ideas, mentors and experience is what makes an education.

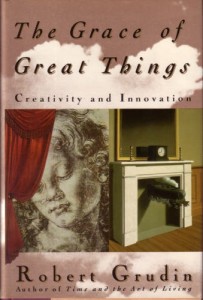

Because of this background, I was excited when I came across a book that explains different types of learning. It doesn’t mention L’Amour, but it could have. The book is The Grace of Great Things by Robert Grudin, and it suggests that there are at least three major kinds of learning.

I. Tasks

First is Task learning, where we have to take action to accomplish a goal. Task challenges include most academic assignments, reading great books, and also simulations, artistic productions such as concerts and plays, and anything else that requires the learner to rise to the challenge of accomplishment.

II. Problems

A second kind of learning challenge is the Problem. “Here the challenge is complicated by unknown factors,” Grudin says. Learners must first think diagnostically and then they follow up with therapeutic responses. When mentors elevate assignments from mere Tasks to full Problems, they invite learners to think more deeply and apply their thinking more broadly.

Note, of course, that Problem learning includes Task skills since the “therapeutic” part of overcoming a learning problem involves tasks. But problems require much more than tasks, since the “diagnostic” portion of surmounting the challenge is fundamentally intellectual. It also involves significant risk to arrive at a diagnostic conclusion and then take action (which may or may not succeed) to apply it.

III. Mysteries

A third type of learning Grudin calls a Mystery. In a sense, this is the highest level of learning challenge because nobody tells the learner that he is completing an assignment. The learner, in the course of learning, comes across a challenge and has to recognize, on his own, that he is facing one. He has to identify that there is a challenge and a need for learning, clearly define what it is and is not, and then turn it into a learning problem and finally a set of tasks.

This teaches leadership skills, independent thinking, creativity, innovation, initiative and originality — all of which are difficult to teach or learn in typical educational settings. Indeed, since these things patently require the original action of the learner, instead of a teacher or boss, they are the hardest of all lessons to “teach”.

This is one reason the great classics are held in such high esteem by those who want to learn leadership. Textbooks, by definition, present Task challenges or Problems. But the real tests in life are Mysteries with multiple problems and tasks inherent — waiting for leaders to detect them and take action. An education built around textbooks mostly trains followers and at best trains problem-solvers.

Leadership Education

Leaders must learn to do so much more — the first and greatest challenge being to recognize that there is a challenge in the first place and then clearly, and accurately, define exactly what it entails.

No such assignment exists in any math textbook I have ever read, for example, but it is the norm in math classics; see Euclid, Nichomachus, Newton, Whitehead, Flatland, Asimov or even Buchanan’s classic essay “Poetry and Mathematics”. Or read Schneider’s A Beginner’s Guide to Constructing the Universe. Other fields, beyond math, follow the same pattern. Grudin takes us through the process of recognizing Mystery as we study:

“Once more, an urgent truth lies in the text. But no one has told us that it is there, much less that finding it is of paramount importance. Moreover, even if we have somehow turned to the correct page and are looking at the right message, there is no certainty that we will recognize it…for it is written in language that, on the surface, looks exactly like everything else in the text.

“The only signal of a challenge, the only factor distinguishing us from the thousand readers who have examined the passage before us and found nothing, is a vague sense of disquiet: a sense either that there is something curiously ‘wrong’ with the text or that there is something strangely wonderful about it. The only way to reduce this subtle code is by looking at language with new eyes, by radically reinterpreting what seems to be common and obvious verbal structures.”

Once a person learns to read this way in the classics, suddenly textbooks, workbooks, technical manuals and all other readings open up and share their “mysteries.” The learner who knows how to read looking for mystery finds much hidden in all writing.

This is not esoteric or apocryphal, it is just that writers naturally communicate more than the mere words they write, and effective readers know how to sense the nonverbal cues as easily as a practiced diplomat knows how to read body language. By the way, this is not a rare phenomenon — the simple word for this is “literacy.”

All who are truly well educated know how to read this way. The fact that so many modern readers are technically literate but not culturally literate in this type of reading was the topic of at least two major bestsellers: The Closing of the American Mind by Allan Bloom and Cultural Literacy by E.D. Hirsch.

The Defining Element of “Classics”

The classics help students, and teachers, reach the level of “mystery” in their studies because we naturally approach Shakespeare, Plato, Beethoven’s 5th or “The Mona Lisa” with the knowledge that generations have considered them truly great.

The classics help students, and teachers, reach the level of “mystery” in their studies because we naturally approach Shakespeare, Plato, Beethoven’s 5th or “The Mona Lisa” with the knowledge that generations have considered them truly great.

We assume there is something deep, profound and perhaps hidden in their work, and so we look for it. Because we look, we find — unless we give up too soon. We wander the Parthenon or Ground Zero expecting to feel greatness, and we are rewarded according to our passion and effort.

“Mystery” challenges are the real assignments in learning, the ones that truly teach us the most important and lasting lessons. “Mystery” pushes us to our own initiative, creativity and innovation — it helps us see more about ourselves. Indeed, it also connects us personally with the topics we are studying — it takes us beyond thinking and analyzing into the realms of feeling and internalizing important knowledge and ideas.

This is all part of a great education, and it is the impetus behind Leadership Education that idealizes the student to come face-to-face with greatness in her studies.

All knowledge is the connected and interrelated, and as Gregory Bateson put it: “Break the pattern which connects the items of learning and you necessarily destroy all quality.”

Note that the starting point to learning at this level is reading the classics, because they are written in a profound, layered and nuanced way that requires dedicated, creative, analytical, correlative, innovative and continual thinking. And after all the reading is done, there is a bonus, which is (in my estimation) the point of it all: those who learn to effectively read, consider and understand the classics genuinely learn to apply such thinking to other facets of their lives, and to the world around them.

IV: Epiphanies

Perhaps the most important benefit of such “Mystery” challenges is that they are often accompanied by epiphany. When we experience an epiphany — a sudden flow of wisdom, knowledge, peace or enthusiasm, a profound breakthrough — we are changed forever. Grudin quotes Michael Polanyi on this point:

“Having made a discovery, I shall never see the world again as before. My eyes have become different; I have made myself into a person seeing and thinking differently. I have crossed a gap, a heuristic gap which lies between problem and discovery.”

It is worth repeating that overcoming any “Mystery” challenge in learning naturally includes Problem learning and Task learning. All three are needed for a great education and effective thinking.

Whether or not your readings, mentors, or even teachers provide “Mystery” learning opportunities, you can search for such learning in all your reading, thinking and studies. This kind of deep thinking is an essential part of truly superb education.

I read once that there are really only 22 plots (some say 20, or even just 7) in human stories and literature. One plot that has always moved me goes like this: young boy faces the challenges of growing up, is guided by parents and mentors, falls in love with books and great ideas, encounters overwhelming life difficulties and rises to overcome them, helps others in the process, becomes the man his early mentors envisioned, and helps make the world significantly better.

This plot plays out in the writings of Homer, Virgil, Shakespeare, Rousseau, Voltaire, Dickens and others. It is also the plot of L’Amour’s greatest books, including, in my opinion, The Walking Drum, The Lonesome Gods, Bendigo Shafter, Fair Blows the Wind, and Sackett’s Land, just to name a few.

Introducing Friends

My son Ammon rarely tells me he is bored, because in such situations I have an amazing knack for finding long and challenging jobs for him to do in the house or around the yard. One afternoon he lost his head for a moment and told me he just didn’t have anything fun to do.

My son Ammon rarely tells me he is bored, because in such situations I have an amazing knack for finding long and challenging jobs for him to do in the house or around the yard. One afternoon he lost his head for a moment and told me he just didn’t have anything fun to do.

I guess I was in a strange mood at the time, because instead of setting him to reorganizing the garage or pruning the trees I smiled and said, “Come with me.”

He must have realized his folly, because he followed me somewhat reluctantly as I walked to the schoolroom in our home. When I stopped in front of my collection of L’Amour books, he looked at me quizzically.

At age 12 he is an avid reader, but I think this was his first introduction to L’Amour. I told him how much I had gained from these old friends, why I called them (and other great books) “old friends,” and I shared several stories about characters that really moved me.

I took each book gently off the shelf as I told him about its characters. We talked for a long time, and both of us were emotional by the time I respectfully returned all the books to their special place in the collection. (In truth, I kept talking until I could see that he was touched, and then I knew it was time to stop and let him experience what he was feeling.)

These books moved me so much as a boy because they were my first introduction to the “mystery” level of learning. I read them for enjoyment, but I learned lessons that I had to sort out for myself. They made me ponder, analyze, consider and think. More to the point, they posed my first great intellectual challenges, because part of the culture they portrayed was in competition with the culture of my home and society.

They made me challenge assumptions, ask questions, and grapple for difficult and uncharted answers. My journey through this long collection presented many tasks, problems and above all mysteries of thinking, and to this day I still find myself debating with L’Amour’s views on many occasions.

“Would you like to read one?” I asked. Ammon nodded his head as he stood in front of the shelves, looking up high and scanning the titles. I left him there, and have enjoyed seeing him quietly carrying around different books over time.

“Would you like to read one?” I asked. Ammon nodded his head as he stood in front of the shelves, looking up high and scanning the titles. I left him there, and have enjoyed seeing him quietly carrying around different books over time.

One day, many months later, I walked into the schoolroom to retrieve a book, and I found Ammon standing in front of the L’Amour shelves trying to pick his next book. I smiled and said, “L’Amour, L’Amour” in my best emulation of Michael Platt. “You can tell a lot about a man by which books are his old friends,” I told Ammon. He nodded, and I left the room with the works of John Adams, another old friend.

(Note: Part of this article is adapted from content found in 19 Apps: Leadership Education for College Students by Oliver DeMille.)

*****************

Featured Article:

Whose Job Is It?

by Rachel DeMille

Among those who enshrine the family and parental roles, the assumption is that it is the role of the parent to see to the education of the child. This seems self-evident in theory; but in practice very, very few parents are involved in decision making about the particulars of their children’s education.

In short: In popular culture today, being fully engaged is defined as parents making sure that assignments (about which they have virtually no say) are completed on time.

On further consideration, I would suggest that there is another answer to this question that is less obvious on the surface, but more in line with the ideal.

Who should be my child’s primary educator?

Or:

Whose responsibility is it to see to it that my child gets the education she needs?

If we are to look to the luminaries in history like Jefferson, Gandhi and Churchill, the answer goes beyond “the parent.”

Certainly the influence of an inspiration and committed parent is felt for generations—but only insofar as the child internalizes the proffered lessons.

So again: Who should be the primary educator?

If educators, scientists and philosophers like Barzun, Erikson and Piaget are to be believed, the answer is: The student.

If a child is to fully achieve her potential, it will ultimately be because of a desire to pay the price for a great education, an allegiance to a cause greater than herself, and a will to consecrate herself to a life’s mission.

Sir Walter Scott said, “All men who turned out worth anything have had the chief hand in their own education.” In this spirit, the purpose of Leadership Education, or TJEd, is to foster self-education in children—and in their parents.

Leadership Education is self-education. It is personalized. It asserts that every child has an inner genius, and that the purpose of true education is to help the child discover, develop and refine that genius. That’s TJEd in a nutshell.

So the role of the parent takes on a new dimension; not: What do I need to teach my child? Or: How do I get my child to learn “x”? But rather: What is my role in helping my children become a successful self-educators? How do I help them discover their purpose in life and get the education they need to accomplish it?

This is how we answer the Who?; and TJEd not only suggests the Who, but the Where, When, How and Why.

By understanding the 4 Phases of Learning and applying the principles of the 7 Keys of Great Teaching, parent-mentors are able to lead out as self-educators and facilitate their children’s efforts as well. And while it may seem like a lot of work to tend to your own education, thousands of TJEd’ers can attest that it’s actually less stressful than trying to copy the conveyor belt.

It’s like hitting the sweet spot on the bat or the tennis racquet—with no additional effort, your speed and accuracy are increased exponentially.

In the words of an old German auto commercial touting its state-of-the-art engineering for power and fuel efficiency: It is easier to pull a car than to push it. In terms of human relations: It is easier to lead a self-educator than to drive him.

And really, all education is ultimately self-education.

****************