Please click on a title to skip to the article you want; or, simply scroll down the page to view them all in order.

Featured Article:

TJEd NEWS:

- New product alert: Upcoming e-book for college students, working title, “19 Apps: Leadership Education for College Students” coming out late summer

- Frequently Asked Questions section under development (please contribute your questions/answers HERE!)

- New centralized page with our free downloads!

- New offering in development: “The Inspired Mind” weekly plan for Core and Love of Learning. Let us know here if this sounds like something we should invest our time in!

- Daily Inspire! emails from Rachel DeMille

******************

Featured Article:

Something to Love

by Oliver DeMille

Educational thinkers as disparate as John Dewey and Maria Montessori taught that the environment in which we learn is just as important (sometimes more important) than the curriculum. We learn from our surroundings, the people in our lives, and the wider world, beyond the assignment or textbook.

Educational thinkers as disparate as John Dewey and Maria Montessori taught that the environment in which we learn is just as important (sometimes more important) than the curriculum. We learn from our surroundings, the people in our lives, and the wider world, beyond the assignment or textbook.

This is one reason the great classics are usually better than textbooks—they are more seamlessly connected with the real world. The environment around us drastically impacts our learning, and this is especially true for children (before puberty brings a heightened ability to think abstractly and compartmentalize).

In TJEd we put a lot of emphasis on helping young people fall deeply in love with learning. Children and youth who genuinely love learning will naturally excel more easily and effectively in their studies.

TJEd also teaches that the most important role of teachers is to inspire students to love learning. This typically comes in three stages:

- first, love of learning

- second, love of study

- third, love of hard, deep, broad and long hours of study

For many young people, the first is a focus for ages 8-12, the second of ages 12-15, and the third of ages 15 and above. For older youth or adults who never fully engaged a deep love of learning during childhood, all three stages are still vital.

A central part of helping students fall deeply in love with learning is giving them something to love. This is, ironically, often easier done than said. In other words, we too seldom put our focus and attention on giving our youth something to truly love. When we pay close attention to this goal, when we give it our focus and effort, it usually isn’t very difficult to find things which they already love and to help them build their educational life around these and related topics.

For example, consider the poetry of Samuel Woodworth:

How dear to my heart are the scenes of my childhood,

When fond recollection presents them to view!

The orchard, the meadow, the deep tangled wildwood,

And every loved spot which my infancy knew,

The wide-spreading pond and the mill that stood by it,

The bridge and the rock where the cataract fell;

The cot of my father, the dairy house nigh it,

And e’en the rude bucket that hung in the well.

Some places are easier to fall in love with than others.

Farms are, as portrayed in this poem, legendary for helping young people love life and love learning. Classics books like Laddie by Gene Stratton-Porter, Little Britches by Ralph Moody, The Lonesome Gods by Louis L’Amour, and many others take the reader through a close tutorial on how reading and the farm life naturally go hand-in-hand.

Many modern home-schoolers and others use the farm environment today as a means of helping young people find passion with various fields of knowledge.

Compare the following, non-farm, account from L’Amour’s The Walking Drum:

“What boy does not know the land of his boyhood? Every cave, every dolmen, every dip in the land and hole in the hedges, and all that lonely, rockbound coast for miles. There I had played and imagined myself in wars, and there I could run, dodge and elude.”

Not everyone can move their family to a farm or the beach, of course. But every family can create an environment in the home and possibly yard that is conducive to inspiring learning.

In our book Leadership Education, we share a number of suggestions on how to do this—including the ideal environment for a classroom, family room, bookshelf and academic-supplies closet.

In our book Leadership Education, we share a number of suggestions on how to do this—including the ideal environment for a classroom, family room, bookshelf and academic-supplies closet.

For example, we described how a leadership education bookshelf has adult books neatly organized on the top rows, youth readings (Scholar Phase) just below, Love of Learning books for ages 8-12 arranged eclectically on the lower middle shelves, and children’s books and child classics (like The Giving Tree or Emma’s Pet) in a messy pile on the bottom shelf.

The paintings or posters on the wall of the schoolroom, and everything else about the learning environment, have a significant, indeed drastic, impact on the educational experience of the children and youth.

In short: Give the student something to love. This is essential to helping them fall in love with learning and, later, hard study. The learning environment matters.

For example, highly entrepreneurial parents often have an office and meeting room in the home, and children in such environments grow up witnessing business meetings, business parties and daily entrepreneurial work taking place.

They overhear business in action, and they grow up feeling that such things are the way life happens. Not only does much of the content of learning rub off, but the feel and culture and a thousand other little things which become part of their educational experience.

This same kind of “transfer of knowledge” occurs in families where the parents are highly artistic, or musical, or scientific/mathematical, or in love with the theater, etc. Actors transfer much about the acting culture to their children. The same is true of many other fields. In sports, a recruit is more highly prized when he is labeled as “a coach’s son.”

This phenomenon is not simply a vestige of the old feudal tradition of children following the same trade as their parents. In fact, in our modern society, few do.

Education encompasses much more than mere book learning and test scores—it is the overall package of one’s abilities, knowledge, character and skills. And all of these are influenced by family.

Moreover, when a student is deeply in love with one thing—from a sport to a topic like math or Shakespeare, to a club or genre of books—it is easier to help inspire her to excellence in other arenas.

I once had a college professor who said that we should only read the “best” books off the approved lists, while another professor taught us that those who read a lot of books of many types are more likely to read a lot more of the “best” books than those who only read from the approved list.

My own experience with students over two decades of teaching proved that the second view is the more effective one. The great educational thinker Jacques Barzun affirmed this in his excellent book Teacher in America. “Readers are leaders,” the old saying assures us.

But more than that, “Readers are readers.”

Likewise, those in love with one area of learning are more likely to fall in love with studying other areas.

Give them something to love. Or, more precisely, help them find something to love. Don’t make the mistake of trying to force them to love something just because you love it—or because you think they should love it to impress someone or for some other inferior reason. Help them find something to love; this is perhaps the most simple and profound method of inspiring.

If your family doesn’t already have some overarching “thing to love,” or if a child seems to be looking for more than the “family love,” just take an hour and brainstorm things your child already seems inclined to love.

Then begin to help her build a broader educational experience around those things. A first step might be for you to study a lot more about something your child seems inclined toward.

The key to great education is falling in love with learning, and the key to falling in love with learning is having something to love.

Parents can greatly help with this (as long as they don’t force love of a topic), and doing so is incredibly inspiring. Moreover, it is fairly simple. Share your loves, and take the time to study more about things your child shows interest in loving.

The ideal is to be able to fall in love with every topic at will, and your example in this is one of the most important lessons you can pass on to your children. Help them find something to love, and keep finding new things you love in your own studies.

Few things make more difference in the quality of a family’s education than the parent’s ability to fall in love with learning and help each child do the same.

- Create an educational environment in your home—no matter where your children attend school—where love of learning is part of the natural atmosphere.

- Set the example to establish a background in your home where all learning is couched in a culture that loves all learning: “In our family we really love learning. Isn’t it wonderful?”

This one shift of culture can do more than anything else to help your children greatly excel in their educational pursuits through life.

Give them something to love.

**************************

Featured Article:

The Elegant Number 9

The elegant number nine is so fascinating and fun to play with. Nine is built out of 3’s, like:

- 3 + 3 + 3

- 3 x 3

There are several Fun Facts for playing with the Number 9. For example, did you know:

1. If you can count up to 10 and back down again, learning to skip-count by 9s (one step away from your times tables) is an easy thing to do.

2. It’s helpful to keep in mind that 9 is one less than 10.

3. The digits of any multiple of 9 add up to 9, or a multiple of 9.

4. Count down from 10s to check your math.

5. If you have two hands with 10 fingers, you already know your 9 times tables.

Let’s start with Fun Fact #1: Counting Up and Down with 9.

On a piece of paper, list the counting numbers, 0 – 9, in a column, like this:

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Now create a second column to the right of the first one, lining up the numbers, counting down from 9 to 0, like this:

0 9

1 8

2 7

3 6

4 5

5 4

6 3

7 2

8 1

9 0

You now have a sequence for skip-counting by nines!

09 (9 x 1)

18 (9 x 2)

27 (9 x 3)

36 (9 x 4)

45 (9 x 5)

54 (9 x 6)

63 (9 x 7)

72 (9 x 8 )

81 (9 x 9)

90 (9 x 10)

But it actually doesn’t stop there; you can start the sequence again, with a minor twist on the very first one:

9 9 = 99 (9 x 11)

10 8 = 108 (9 x 12)

11 7 = 117 (9 x 13)

12 6 = 126 (9 x 14)

13 5 = 135 (9 x 15)

14 4 = 144 (9 x 16)

…and so on.

If you chant them out loud you can really hear the rhythm and pattern, and anticipate the next one coming. Try it and you’ll see what I mean!

Here’s where we bring in Fun Fact #2: 9 is one less than 10.

Like I mentioned at first, 9 is one less than 10. It’s a fairly simple thing to add 10 to a number—particularly if it’s only 1 or 2 digits.

For a 1-digit number like 2 or 7, simply put a “1” next to it on the left, indicating that your tens column has grown by 10. Thus 2 becomes 12 and 7 becomes 17.

So skipping to the next number in the 9’s sequence is easy when you just add 10 and then take one away.

Like:

- 9 + 10 = 19, and 1 less is 18—so 18 is the next number when skip-counting by nine.

- 18 + 10 is 28, and 1 less is 27—so 27 is the next number in the sequence when skip-counting by nine.

But what if you’re not looking at the whole sequence, or counting up from a lower number?

What if you just think you know the answer to 9 x 7, but you’re not 100% sure?

Time for Fun Fact #3: The digits of any multiple of 9 add up to 9 (or a multiple of 9).

There’s a really easy way to check your work, so you can know if you’ve made a mistake on a particular multiple of 9 without seeing the whole sequence. All you have to do is add the digits together.

When you add them and your answer is “9”, or a multiple of 9 (like 18 or 27) then you know your number is in the family of nines. If not, it’s not. How cool is that?

So, in the case of 9 x 7: if you guessed 63, and then added the digits together:

6 + 3 = 9

You know for sure that 63 is, in fact, a multiple of 9. (Of course if you guessed that 63 is the answer to 2 x 9, you’re still mistaken, LOL.)

Let’s watch that in action, so you can see what I mean…

09 0 + 9 = 9

18 1 + 8 = 9

27 2 + 7 = 9

36 3 + 6 = 9

45 4 + 5 = 9

54 5 + 4 = 9

63 6 + 3 = 9

72 7 + 2 = 9

81 8 + 1 = 9

90 9 + 0 = 9

99 9 + 9 = 18 (9 x 2)

108 1 + 0 + 8 = 9 (or 10 + 8 = 18 = 9 x 2)

117 1 + 1 + 7 = 9 (or 11 + 7 = 18 = 9 x 2)

126 1 + 2 + 6 = 9 (etc., as above)

135 1 + 3 + 5 = 9

144 1 + 4 + 4 = 9

Isn’t that amazing? Numbers are so elegant and fun to play with! I love finding patterns like these.

Fun Fact #4: Count Down from 10s to Check Your Work

You know what? There’s another really neat thing about 9’s. It’s a trick that you’ll use for other fact families as well, called “counting down.”

Counting down works in this way: since you already know that ten times something is just to add a zero on the end, you have a really solid fact family to work from. Did you know that 9 times something is just ten times, minus that same number? Here’s some examples:

10 x 3 = 30

9 x 3 = 10 x 3, minus 3, or: 27

10 x 6 = 60. If you take six away, you are left with 54, or 9 x 6 = 54. Do you see how that works?

It’ll work no matter how small or large the number is.

The next pattern is so very cool, it’s right on the tips of your fingers…

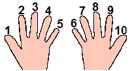

Fun Fact #5: Your 10 fingers hold the key to 9 times tables.

This trick works for 1 x 9 through 9 x 9.

Did you know that you have the nine times tables wrapped around your fingers? In the palm of your hands? Here’s what I mean:

Did you know that you have the nine times tables wrapped around your fingers? In the palm of your hands? Here’s what I mean:

First, hold both your hands out in front of you, with palm open and facing you. Now, starting with your left thumb, number your fingers from left to right, ending on the right thumb. In this way, your left pinkie is 5 and your right pointer if 9, for example. Get it?

Okay. Now, if you want to do 1 x 9, you bend your #1 finger (left thumb) in toward your palm, like this:

Okay. Now, if you want to do 1 x 9, you bend your #1 finger (left thumb) in toward your palm, like this:

See what’s left? Nine little fingers still standing. That means 1(the left thumb) x 9 = 9 (fingers up). Easy, right? But you already knew that one.

Let’s see if we can make it work for another one. Start again with all your fingers extended. Now bend your left middle finger (that’s #3!) toward your palm, like this:

Let’s see if we can make it work for another one. Start again with all your fingers extended. Now bend your left middle finger (that’s #3!) toward your palm, like this:

This means 3 x 9. And what are you left with? Two fingers standing on the left, and seven (count’em—the left ring and pinkie fingers and all the fingers on the right hand) standing in a row on the right. So on the left of the bent finger we have a 2, and on the right of the bent finger we have a 7. Put them together and you have your answer: 2-7. 3 x 9 = 27. Isn’t that cool?

Let’s try one more. Start again with all your fingers extended, palms facing you. Now bend your right pinkie down, like this:

That finger represents #6, remember? So this is the trick for 6 x 9 (or 9 x 6, same thing—remember the commutative property of multiplication). On the left of the bent finger are 5 fingers standing, and on the right of the bent fingers are 4 fingers standing. 5 and then 4—our answer is 54. 6 x 9 = 54.

That finger represents #6, remember? So this is the trick for 6 x 9 (or 9 x 6, same thing—remember the commutative property of multiplication). On the left of the bent finger are 5 fingers standing, and on the right of the bent fingers are 4 fingers standing. 5 and then 4—our answer is 54. 6 x 9 = 54.

There is so much more fun to be had with numbers, the things they build and the patterns they create. Next time maybe I’ll share with you what pretzels, fudge, Mozart and gravel have taught me about Prime Numbers….

***********************

Rachel DeMille is developing a new Core and Love of Learning lesson plan resource for charter and homeschools called, “The Inspired Mind.” Watch for announcements from TJEd.org on how to take part, or contact Rachel here to be put on the notification list.

Rachel DeMille is developing a new Core and Love of Learning lesson plan resource for charter and homeschools called, “The Inspired Mind.” Watch for announcements from TJEd.org on how to take part, or contact Rachel here to be put on the notification list.

[/fusion_text][/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]