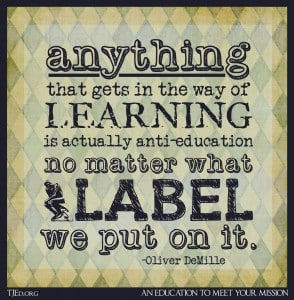

by Oliver DeMille

Like everyone, I sometimes make mistakes. Sometimes I’m wrong. Sometimes I make a rash decision or a careless comment. And like everyone, I suppose, my kids are pretty clear on the fact that I’m fallible.

And I’m okay with that.

Not that I’m indifferent or casual about getting it right; but when mentoring within the context of Leadership Education, there comes a time when being wrong can be really, really right.

Getting Right Wrong

See, if we (as mentors) are never wrong, we can feel like know-it-alls, be emotionally inaccessible or intimidating to our students, or seem intellectually closed and unteachable.

If we’re always right, we run the risk of teaching our students to trust our experience, our reasoning, our expertise, rather than learning to think for themselves and learning to trust their inner light.

If we’re always right, we foster an authoritarian value system where they hope to one day graduate to be the mentor-bully in our place, or perhaps worse, where they learn to always look for and depend on someone else to tell them what to think and do, or to validate their conclusions and efforts.

And, as our dear friend Donna Goff pointed out, if we are always right, we groom our students for arrogance.

These are not positive mental postures, and definitely not what we want to communicate to or model for our children or students.

Getting Wrong Right

But what if we’re wrong sometimes? How do we handle that?

Do we show appreciation when a student or colleague supplies us with information that contradicts our previous assertions?

Do we celebrate the moments when our students respectfully disagree?

Do we effectively communicate to our mentees that we welcome their dissenting opinions, that we enjoy it when they challenge assumptions and explore new avenues of thinking? Even when they might not be effective or well thought out? Even when it’s just discovery, without a well-founded direction?

Do they feel safe to try their wings, so to speak, with us, without paranoid avoidance of being “The Dreaded Wrong!”?

If we’re comfortable with them seeing us be wrong sometimes (’cause we are, whether we’re comfortable with it or not!), it helps them to venture beyond what’s “safe” and “approved” and really begin to innovate and synthesize new ideas.

For Example

A couple of weeks ago I wrote a newsletter which cited an article that was, to put it bluntly, wrong. Within a few hours I had several requests for additional sources, and within the week I had a very well reasoned rebuttal from one subscriber.

Apart from being disappointed in my misstep (I should have verified the material, not just believed the national news source where I read it), I was really pleased with the response! These readers were, without exception, very respectful and constructive in their dissent, and represented that they really were on the path of Leadership Education.

They expected of themselves to think independently, to draw their own conclusions, to seek and to disagree in the arena of ideas without making personal attacks or unnecessary “us-them” divisions. They were seekers of truth, regardless of the source or the tone of delivery. I am honored to be associated with such individuals, and it inspired me to dig deeper–always.

Go For It!

Isn’t this the kind of response we hope for from our children, our youth, our students and mentees? Don’t we aspire to have them exceed our limitations, and unleash their genius on the world without being hobbled with our weaknesses, our imperfect understandings, or whatever else makes us less than the ultimate ideal? Don’t we want them to truly, really, take risks and think independently?

We can’t avoid being wrong once in a while. But let’s fail spectacularly, and do wrong right.

****************

For more ideas on developing your mentoring skills, see The Student Whisperer.

Oliver DeMille is the co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Oliver DeMille is the co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

He is the New York Times best-selling author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom, and FreedomShift: 3 Choices to Reclaim America’s Destiny.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through Leadership Education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

This morning while teaching a class, I asked the students a question which had a possibility of one of two choices for the correct answer. One of the students offered one of the choices. I thanked the student and asked if the other choice could be the right one. Another student offered under his breath, “Well, it’s obviously the second choice since you suggested it.”

The reality was, and I explained it to the class, that I was not sure of the correct answer myself. I was not “baiting” them with the answer. I wanted to learn along with them.

I then asked them where they thought they could find the correct answer and we used the dictionary of our “primary source” to quickly look up the answer together. We created a nemonic to help us remember it next time and we moved on.

Next class time I will ask this question again. I will point out that those who remembered the right answer invested something in finding the answer in the first place, that is why they remembered.

I hope that despite their public school training, through examples like this, they will learn that I am trying to be a mentor, not a teacher.

“Let’s fail spectacularly, and do wrong right.” LOL! I love it!

I think of the speech by President Teddy Roosevelt know as “the man in the arena”

It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.

Fails while daring greatly, that is what failure looks like for myself and my children