Mazes and Levels

Most organizations start out with a great mission, then run into challenges and focus on survival, then want to grow and shift their focus to trying to impress the world.

Most organizations start out with a great mission, then run into challenges and focus on survival, then want to grow and shift their focus to trying to impress the world.

Eventually they become a roadblock to the very great mission and goals they set out to promote in the first place.

This pattern is clearly followed by most educational organizations. “Institutionalism” occurs at the point where the goals of the parent or school are a higher priority than the quality of each student’s learning.

Losing Sight

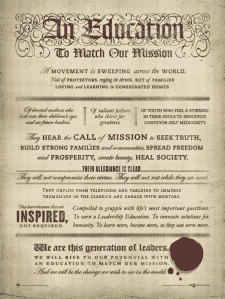

Consider public schools. They were originally set up by the American founding generation with one major goal—to ensure that every student and family had the opportunity to educate real citizens, the kind who read the same things and think about the same things as any President, Senator, Governor, Judge or major business leader.

The idea was that such people would maintain the nation’s freedom, and be the most important part of national security and strength. A highly educated and wise electorate would ensure America’s future.

In fact, the first law passed by the U.S. federal government under the new Constitution of 1789 was the Northwest Ordinance—which outlined the kind of education any territory would have to provide in order to become a state.

Of course, the term “public school” in this era meant local and community schools run by a committee of parents or school board made up of a few elected local parents, not a professional bureaucracy scrambling to meet all the mandates out of Washington D.C. To see how such early schools provided truly excellent education (generally much better than our schools today), see the educational model found in literature like Gene Stratton-Porter’s Laddie, the Little House series, Ralph Moody’s Little Britches, L’Amour’s Bendigo Shafter or Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, among others.

Or simply read The Federalist and note that it was written in the newspaper for regular farmers, merchants and workers. If this was the regular educational level of the people, their educational model was clearly superb. The same is true of the Lincoln-Douglass Debates.

The Goals Left Behind

Over time schools adopted the Horace Mann approach and began focusing less on the quality of each student’s learning and more on the survival and conformity of the school system and the teachers as a profession. Then they selectively applied the ideas of Dewey to emphasize a mass, bureaucratized model with the main goal of impressing the world. Personalization, individualization, and the primacy of quality learning were largely left behind.

To see how this pattern progressed in other places around the world, consider the educational models in Jane Eyre or anything by Dickens. Read George Turnbull or Potok’s The Chosen for additional examples.

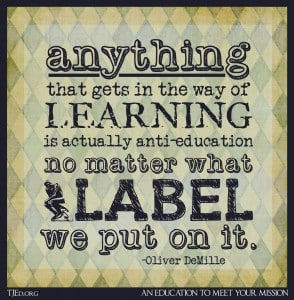

Today we live in the fourth step of the pattern, Institutionalism. Most schools are so focused on things that have little to do with each student’s truly great learning that they frequently get in the way of this very goal. In fact, this goal is usually entirely missing now.

Sadly, parents who homeschool and educational reformers who set up alternative private and charter schools are often tempted in the same way. They make difficult, even heroic, educational sacrifices and choices in order to provide truly excellent personalized learning for each student, then face the challenge of financial survival—and/or decide they want to become impressive to others—and give in to an increasingly conveyor-belted model. This usually happens in small steps, each seemingly insignificant but over time creating an inferior learning model.

The problem in all this is that factory belt approaches to education always emphasize several goals that are deemed more important than the individual learning of each student. This is the downfall of almost all modern education.

Answering the Question

Parents and the rare teacher or administrator who see past this natural tendency to lose the true meaning of education are the real educational heroes of our time. They provide truly excellent education, which is always (always!) focused on individualized and personalized learning for each student.

Parents and the rare teacher or administrator who see past this natural tendency to lose the true meaning of education are the real educational heroes of our time. They provide truly excellent education, which is always (always!) focused on individualized and personalized learning for each student.

This is the key to a great home, a great school, and, for those who choose it, a great homeschool.

In short, has anything gotten in the way of your kids’ personal learning, love of learning, passion for learning, and enthusiastic habit of daily learning?

Good parents, teachers, and administrators ask themselves this question every week or two, or even every morning and afternoon, and take action to ensure that personalized great learning for each student is the central point of all their efforts.

If the answer to this question is ever “yes,” or even “maybe,” immediately find a way to get the offending goal or distraction out of the way.

Great mentors focus on the student, and on helping each learner truly excel. Institutionalism always tries to thwart quality, even in homeschools.

Beware anything that lessens the quality of learning or each child’s passion to learn today.

Moreover, don’t wait to notice such problems. Be vigilantly on the lookout. Expect such distractions to come, and be ready to reject them. If you are helping a student get a great education, there will be many competing attempts to turn your attention away from great, quality, individualized learning. Keep your focus on what really matters.

Johnny’s learning. Mary’s excitement to learn today.

Get this right, and their education will flourish!

Oliver — Might you be able to give a few real world examples of a some typical distractions and faulty goals that can pull a homeschooling family away from individualized, personalized learning? I’m finding I could use specific examples to help me truly “see” your point. I appreciate your time and input.

Thank you, Alison

Those first few paragraphs also apply to religious institutions. All institutions are in some degree or another immoral, and in the words of J. Bonner Ritchie we must learn to “use the institution rather than be used by it.”

Interesting insights, as always, Oliver. I just have one additional thought, and perhaps a unique vantage point.

There are two main ways to demonstrate educational leadership: (1) as an educational philosopher, develop and articulate educational principles; or (2) as an educational entrepreneur, build educational organization(s).

It seems to me that educational philosophers are often critical of educational entrepreneurs because these leaders wind up making compromises to secure the good of their organizations at the expense of their students. On the other side of the spectrum, educational entrepreneurs are often critical of educational philosophers because philosophers sit at a desk and pontificate rather than actually building something.

In my opinion, while both criticisms are often true, this kind of attitude causes an unfortunate polarization and unnecessary contention. I’m sure you’d agree that we need philosophers and entrepreneurs. Meaningful educational reform must strike a balance between these two forms of leadership. Organizations develop expertise, efficiency, peer community, and broad experience that is simply unavailable to individuals and that can greatly benefit students. At the same time, as TJEd articulates so brilliantly, there has never been and never will be a replacement for an individualized, mentored educational path.

At Williamsburg Academy (WilliamsburgAcademy.org) and Intermediate (WilliamsburgIntermediate.org), we are working hard to find this sweet spot, and we are part of hundreds of other organizations around the U.S. seeking to find meaningful (and scalable) reforms. Many of these reforms, by necessity, must be wrought by organizations rather than mere articulation of pure educational philosophy.

We have and continue to find inspiring educational ideas in the TJEd community. Thanks for all you do.

James